By someone who knows how absence writes itself into the body like a second language

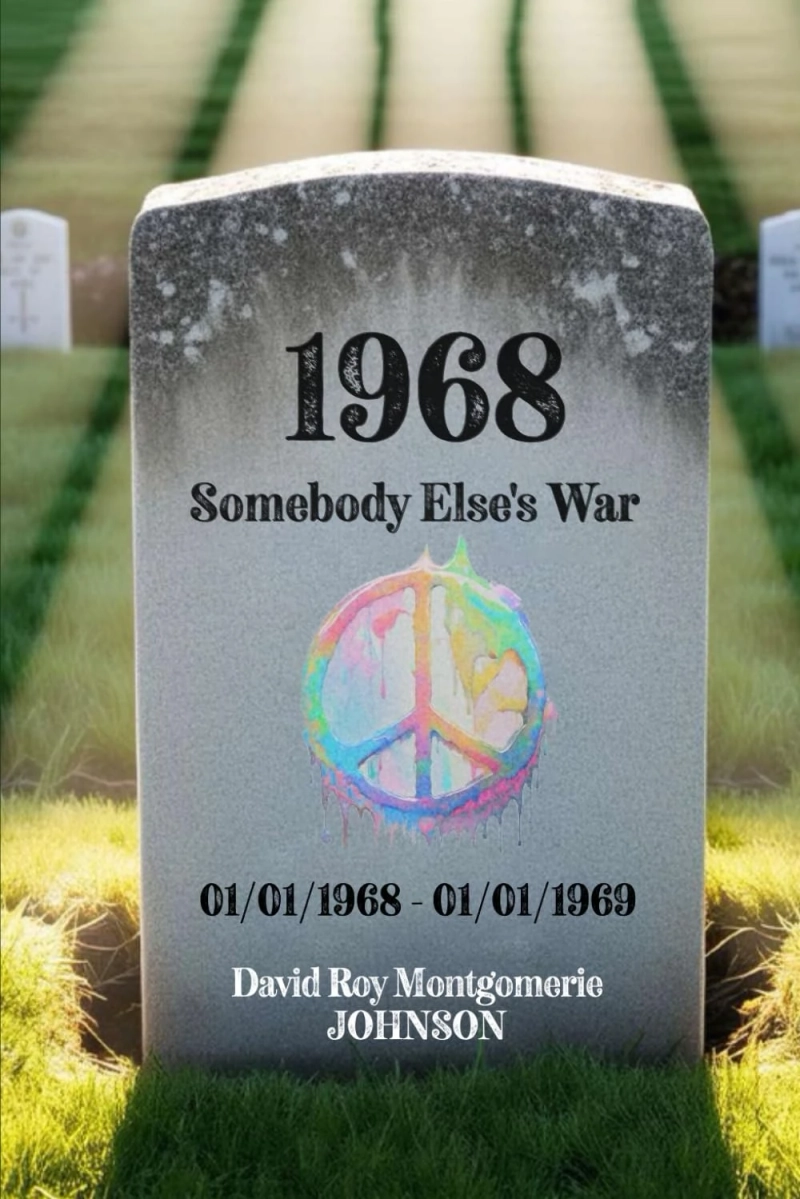

What do we inherit when no one talks about the past? What passes down through blood when words fail, when stories go untold, or worse, unacknowledged? In David Roy Montgomerie Johnson’s Somebody Else’s War, these questions hum beneath every page like a distant frequency, never quite audible but unmistakably present. This isn’t a book about war in the conventional sense. It’s a book about what war leaves behind, about the absences it plants in people and places, about the space between knowing and not knowing.

Set in 1968 in a fictional Canadian town called Newport on the Lake, Johnson’s novel builds itself out of fragments. Newspaper headlines, gossip, drifting conversations in diners. It’s a patchwork of voices and perspectives, all loosely held together by the gravitational pull of a town that seems to be disappearing even as it stands still. This isn’t a story with a tight spine or a central drama. Instead, it’s more like a weather pattern, slow-moving, unpredictable, and deeply sensitive to shifts in emotional air pressure.

At the centre, or maybe just slightly off-centre, is Captain Sammy Enfield, a former Marine now sleepwalking his way through the bureaucracy of small-town policing. He’s not a protagonist in the traditional sense. He doesn’t grow. He doesn’t change much. But what he does, what he embodies, is central to the novel’s real preoccupation: inherited silence. He’s the product of wars that weren’t his to choose, and his son, Warren, now faces another. The generational handoff isn’t about glory or tradition, it’s about trauma deferred.

Sammy’s war is over, technically. But no one tells the body that. He wakes from dreams he can’t explain, walks through the snow in a daze, and struggles to finish sentences when faced with real intimacy. His estranged wife, Becky, sees it more clearly than he ever could. In one of the novel’s most quietly devastating passages, she lays it all out: five generations of Enfield men who never met their fathers because they all died in wars before their sons were born. Warren, her boy, is the first to break the chain. And the possibility that he, too, might vanish into the same void, that he might become “somebody else’s” war, is almost too much to bear.

This is what Johnson does so well. He writes about grief not as a spectacle but as sediment. Grief is something that accumulates over time, layered, geological. It’s not loud. It doesn’t cry out for attention. It just sits in people, quietly reshaping the landscape of their lives.

That landscape includes not just individuals but an entire town. Newport on the Lake is a place haunted by what it used to be: a lakeside jewel for wealthy Americans that has long since been abandoned by fashion, commerce, and history. Its courthouse still stands, but its clocks don’t work. Its mayor holds court with a kind of performative bluster that feels like self-parody. And yet, for all its decay, the town endures, not because of any great civic pride but because people don’t know where else to go.

There’s something profoundly human in that. Johnson’s characters don’t cling to Newport because they love it. They cling to it because leaving would mean admitting how much they’ve already lost. It’s a form of denial, yes. But it’s also a form of love. Or maybe grief masquerading as love.

The characters themselves are masterfully drawn in their contradictions. Gunner Simpson, for instance, might be the most emotionally fluent man in the book. A former intelligence operative (maybe), now living quietly with his children, Gunner seems to understand that the real inheritance he can offer isn’t knowledge or money or legacy, but steadiness. Wisdom. The ability to speak without posturing. In his quiet walks with his son, Boy, he passes along something rare and radical: a blueprint for masculinity that isn’t built on dominance or silence.

Boy, like Warren, like many of the younger characters in the book, represents a pivot point. The generation raised by men who wouldn’t, or couldn’t, explain themselves. The children of shadows. You get the sense, reading these young men, that they’re trying to trace their lives along a map that was never drawn for them. That they’ve inherited not just genes but absences.

And then there’s B11711, the prisoner, the pedophile, the embodiment of what happens when absence metastasizes into hatred. He is the novel’s most unsettling figure, not because he’s a caricature of evil, but because he is so precisely calibrated. His inner monologues reveal a man so deeply isolated, so rotted by resentment and entitlement, that he begins to hallucinate his own moral superiority. He is the shadow version of every man in the book who fails to reckon with his own grief.

It’s tempting to call Somebody Else’s War a quiet novel. Its chapters are often brief. Its scenes unfold slowly, often without resolution. But calling it quiet doesn’t do justice to its emotional velocity. Johnson writes with restraint, yes. But there’s a fury underneath, grief too big to name, too old to address directly. And so the book sidesteps, circles, pauses.

What results is not a political novel, exactly, though politics flicker in the margins. Vietnam is ever-present, but so are the limitations of civic life: a clock tower that keeps being crashed into, by-laws about horses, and passive-aggressive memos. The absurdities of small-town governance are not just comedic detours, they’re coping mechanisms. They’re the rituals people cling to when meaning is scarce.

If there’s a thesis to the novel, it might be this: that memory is not what we remember but what we live inside of. These characters live in memory even when they can’t articulate it. They walk through streets built by people they’ve forgotten. They grieve losses that haven’t fully arrived. They love without saying it, parent without guidance, survive without celebration.

And somehow, that survival matters. It doesn’t redeem the war. It doesn’t make the trauma noble. But it offers something else: continuity. A line not yet broken. A scar that doesn’t define the face only marks it.

By the end of the novel, there is no grand gesture. No healing epiphany. But there are moments, tender, clumsy, human, that land with the force of a revelation. A father is sitting on a bench beside his son. A woman names her grief in a waiting room. A waitress kissing a scar because it’s part of a man she wants to know.

These aren’t solutions. They’re acknowledgments. And in a world where silence has been passed down like a curse, acknowledgment might be the bravest act available.

Somebody Else’s War isn’t about war at all, not really. It’s about what fills the air when the battles are over, about how we inherit both the damage and the dignity of the people who came before us. It’s about how absence moves through time like the weather, shaping us, changing us, and making us reach, sometimes blindly, for connection.

And maybe that’s what makes it beautiful. Not its plot. Not its characters. But it's patience. It's willingness to sit with what we’ve lost and still tell a story anyway.